For me, the deepest existential source of coming to terms with white racism is music. In some ways, this is true for black America as a whole, from spirituals and blues through jazz, rhythm and blues, and even up to hi-hop.

From the very beginning, I always conceived of myself as an aspiring bluesman in a world of ideas and a jazzman in the life of the mind. What is distinctive about using blues and jazz as a source of intellectual inspiration is the ability to be flexible, fluid, improvisational, and multi-dimensional — finding one’s own voice, but using that voice in a variety of ways. (pg. 114)

American musical heritage rests, in large par, on the artistic genius of black composers and performers.

This rich tradition of black music is not only an artistic response to the psychic wounds and social scars of a despised people. More importantly, it enacts in dramatic forms the creativity, dignity, grace, and elegance of African Americans without wallowing in self-pity or wading in white put-down. (pg. 116)

forms the creativity, dignity, grace, and elegance of African Americans without wallowing in self-pity or wading in white put-down. (pg. 116)

Obama says Jeremiah Wright is angry because he’s part of an older generation. That’s not true. Walk the streets of Brooklyn. The young brothers and sisters are angry and full of rage right now. Katrina was just three years ago. You and I are still full of righteous indignation. We didn’t need to grow up under Jim Crow to be like Bigger Thomas in terms of the rage simmering inside.

The question is, How do you express your righteous indignation? The assumption and the dominant white perspective is that, if you have an angry Negro, that Negro’s anger is somehow unjust. That’s inaccurate. You can have rage against injustice and still recognize that not all white folk are complicit. (pg. 141-142)

Black women are going to be the crucial part of the next wave of our collective leadership. (pg. 149)

Love helps break down barriers, so even when black rage and righteous indignation have to look white supremacy in the face — in all its dimensions that still persist — the language of love still allows black brothers and sisters to recognize that it’s not all white people and it’s not genetic.

White brothers and sisters can make choices. John Brown was part of the movement. Tom Hayden is part of the movement because it’s all about choices, decisions, and commitments. No one is pushed into a pigeonhole or locked into a convenient category. That is why the ability to love and be loved in the highest sense is so crucial. (pg. 161)

American culture seems to lack two elements that are basic to racial justice: a deep sense of the tragic and a genuine grasp of the unadulterated rage directed at American society. The chronic refusal of most Americans to acknowledge the sheer absurdity that a person of African descent confronts in this country — the incessant assaults on black intelligence, beauty, character, and possibility — is not simply a matter of defending white-skin privilege. It also bespeaks a reluctance to look squarely at the brutality and tragedy of the American past and present.

Such a long and hard look would puncture the life-sustaining bubble of many Americans, namely that this nation of freedom-loving people and undeniable opportunity has committed unspeakable crimes against other human beings, especially black people.

Reverend Jeremiah Wright is my dear brother. Recently he has been anointed as the media’s latest incarnation of the “bad” Negro. Whether in slavery or in black communities under Jim Crow — bad Negroes are “out of control.” Jeremiah Wright speaks his mind. Remember, all of us are cracked vessels. Jeremiah Wright deserves criticism, but it should be justifiable criticism. For example, Reverend Wright’s claims about AIDS and HIV are wrong.

I’ve had the opportunity to speak in Reverend Wright’s church on many occasions. I’m so glad whenever his full quote is played or published because any God worthy of worship condemns injustice. When he says, God damn America — killing innocent people. God damn America for treating her citizens as less than human. That is true for any nation. We must never put the cross under the flag.

Wright is a prophetic Christian preacher, therefore to him every flag is subordinate to the cross. If you believe that America has never killed innocent people, then God never damns America. We know god damns slavery, Jim and Jane Crow, the hatred of gays and lesbians, anti-Semitism, and anti-Arab “terror” bias in America. God is a god of justice and love.

What Wright was trying to address is the degree to which there is still injustice in America. Never confuse this criticism with anti-Americanism. Any resistance to injustice, be it in America, Egypt, Cuba, or Saudi Arabia, is a God-driven activity because righteous indignation against the cruel treatment of any group of people is an echo of the voice of God for those of us who take the cross seriously. (pg. 167-169)

To deny death is to deny history, reality, and mortality. We’re most human when we bury our dead, when we stand before the corpses of our loved ones, forced to bring together the three dimensions of time: past, present, and future. (pg. 184)

I think highly of the pacifist tradition in christendom. I do not agree with it. I am not persuaded by it. But I think respect is due. I do not think Christian pacifists will ever have the kind of impact on history that many of them profess to have. Yet I respect their views. So when I hear Archbishop Tutu and many others argue for nonviolence, I respect them.

One should, on the principled ground, attempt to exercise and realize all forms of nonviolent resistance before one even remotely considers the discussion of violent resistance and armed struggle. One must examine the history of a country carefully and see what possibilities there have been nonviolent resistance and what impact nonviolent resistance has had.

If we in fact, discover that nonviolent resistance in its most noble form has been crushed mercilessly by the rulers, then it raises the possibility of forced engagement in armed struggle. Indeed, this is in no way alien to the Christian tradition. On the other hand, one should never view armed struggle as a plaything. One should not romanticize or idealize it at all. On the contrary, one should carefully and thoroughly think through whether it can have the impact and effectiveness that one desires. (pg. 187)

There is always a fundamental tension between a commitment to truth and a quest for power. The two are never compatible. It could be Socrates, Jesus, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Fannie Lou Hammer. You always need a prophetic critique of those in power. Power intoxicates. Power seduces. Power corrupts. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. There is always a need for somebody to tell the truth to the powerful. (pg. 208)

When you talk about hope, you have to be a long distance runner. This is again so very difficult in our culture, because the quick fix, the overnight solution militate against being a long distance runner in the moral sense — the sense of fighting because it is right, because it is moral, because it is just. Hope linked to combative spirituality is what I have in mind. (pg. 209)

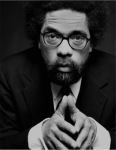

Welp. I did an interview with Cornel West and

Welp. I did an interview with Cornel West and

He has written

He has written  Maybe we need to declare war on the nation’s healthcare system that leaves the nation’s poor with no health coverage? Maybe we need to declare war on the mishandled educational system and provide quality education for everybody, every citizen, based on their ability to learn, not their ability to pay. This is a time for social transformation.”

Maybe we need to declare war on the nation’s healthcare system that leaves the nation’s poor with no health coverage? Maybe we need to declare war on the mishandled educational system and provide quality education for everybody, every citizen, based on their ability to learn, not their ability to pay. This is a time for social transformation.”